In this profession it’s easy to fall into this trend of painting certain muscles as “good” and others as “bad”. By doing this we fall into this comfortable, yet short sighted pattern of arbitrarily training and over emphasizing certain muscle groups by default. Rather than letting the context of the situation inform you on whether more of something is needed or not.

The rotator cuff, or muscles of the posterior shoulder girdle fall into this heuristic category of “good“. When working with someone with shoulder issues, or an overhead athlete, by default a clinician will often fill a training regiment with exercises with the intent of increasing the amount of activity in this region. Largely due to this general narrative surrounding this anatomical region that the more training through this area the better! (This is another lengthy conversation that probably deserves a series of posts).

Now as some people are reading this, I’m sure they have this notion that I am now trying to point the finger at these muscles and put them in the “bad“ category. Rather, I’m writing this to point out the issues with this binary thought process. There needs to be a gradient of appreciation for all things in this profession, certain muscles or exercises are no different. Understanding the context of an individual situation is what should guide the judgement of “good“ vs “bad“ rather than any predetermined notion.

Many of us are familiar with scapulohumeral rhythm, as the arm moves up, so does that shoulder blade, this is one piece that enables the upper limb of humans to be able to move into more spaces compared to other species. Often times, as practitioners we discuss this as relevant to enhancing movement between the scapula and the ribcage in order to improve upon overall range of motion of overhead positions. However, we shouldn’t overlook the necessary space and movement between the humerus and scapula to also maximize overhead motion.

An extreme example of this would be a patient who just recently has had a surgically repaired rotator cuff. Often times we I would work on the classical passive and active assisted range of motion activities for a post-surgical shoulder case (doorway pulleys, cane assisted motions, etc). What I would observe with some of these patients is that they would be competitive to get their arm and hand as high as they could, but I’d see much more motion through their thorax, and upward rotation of the scapula, but the space between the humerus and the scapula wouldn’t change.

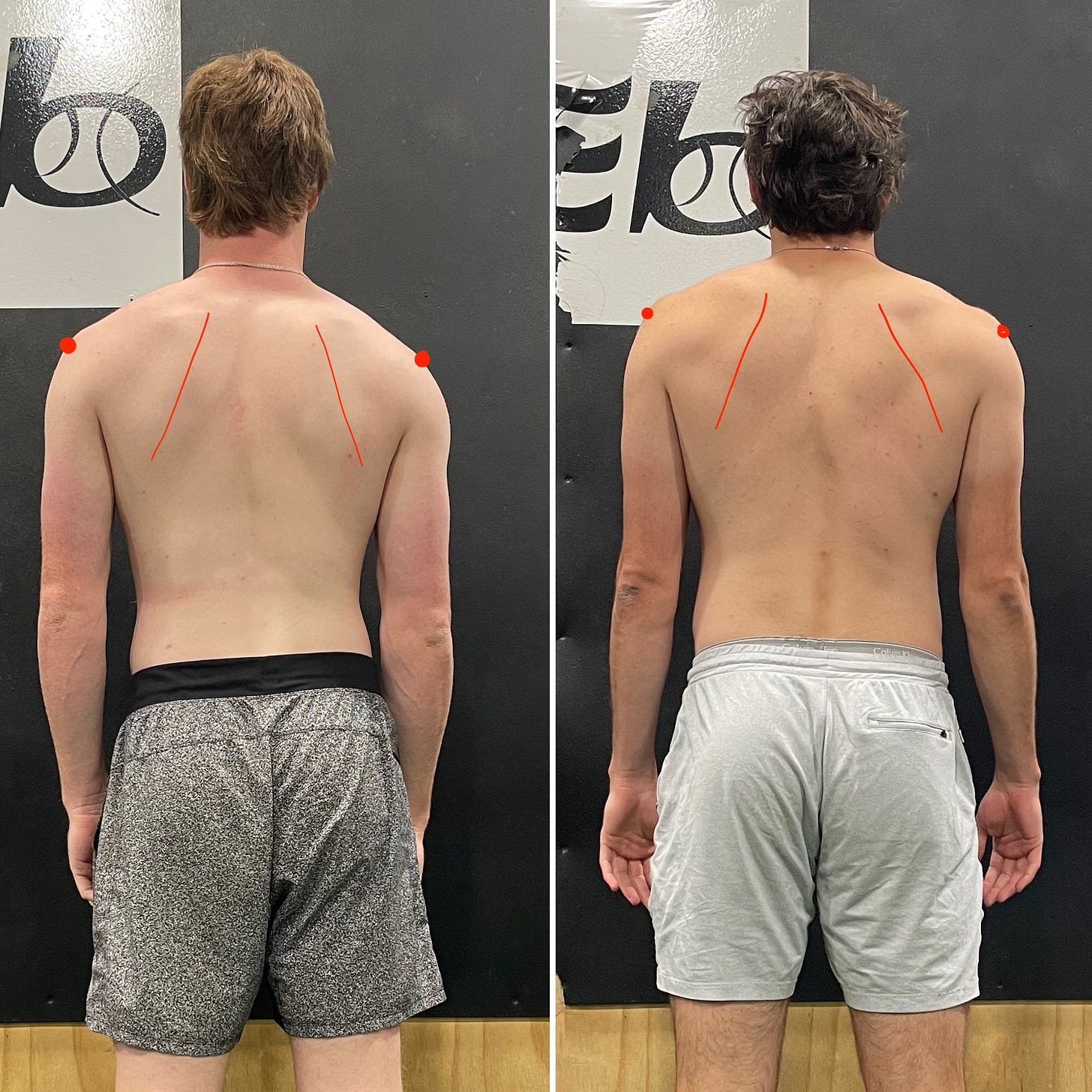

Likewise, with baseball players, I have seen decreased overhead motion and decreased shoulder IR, as well as visual observations of less space between a humerus and scapula. concentric muscle activity operates to bring both attachment sites together. Often these muscles are portrayed as influencing just the humerus, when in reality they can have a significant impact on the position of the scapula as well. Potential issues with their throwing mechanics could include a reduction in the height of their arm slot, or an elbow that is in front of the humeral head at max layback.

In the video above, the goal of this technique is to increase the concentric orientation of the muscles of the posterior scapula (infraspinatus, teres minor, trees major, posterior deltoid, proximal tricep) there by increasing the space between the scapula and humerus and reducing the pressure on the posterior joint capsule of the GH joint. Expected improvements in ROM would be flexion, abduction, and internal rotation.