The bicep tendon is another structure that gets a lot of attention in the baseball world. Mainly the long head of the bicep, and mainly as way to quickly brush off and put a name to the issue of anterior shoulder discomfort in an overhead athlete.

Sometimes it deserves some blame, sometimes it doesn’t. I think highlighting some anatomy and changing the perspective of how, as well as, where it can have an influence can be beneficial to know when to pass blame on it.

Anatomy:

Textbook anatomy of the bicep brachii has its distal attachments to the radial tuberosity and the bicipital aponeurosis, more proximally it splits into long and short head, attaching into the superior glenoid and coracoid process respectively.

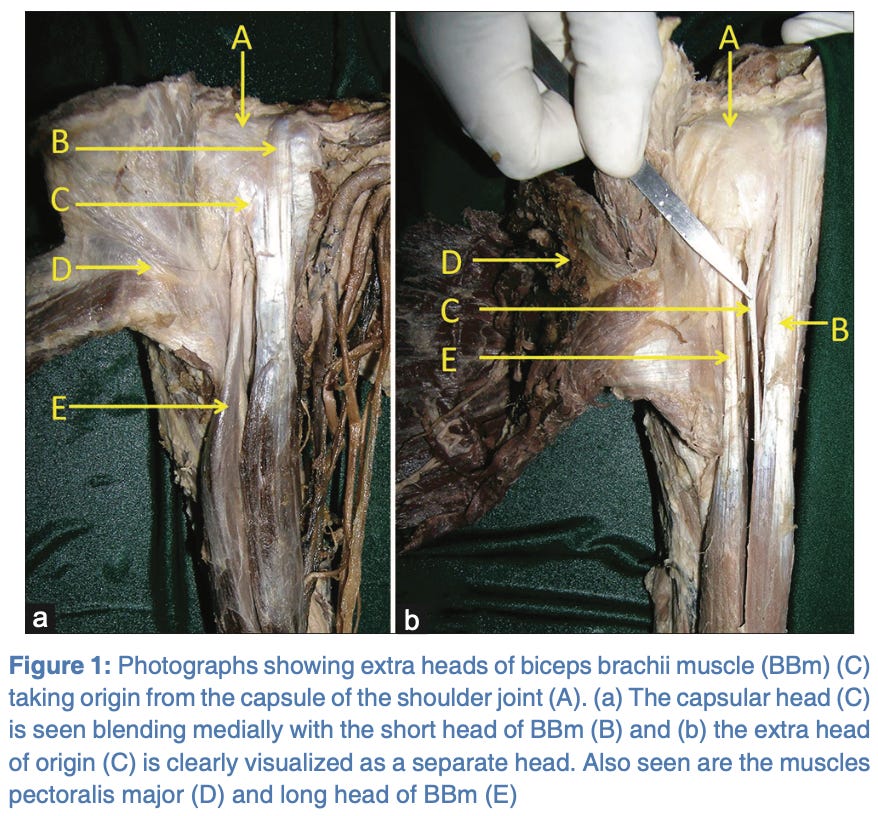

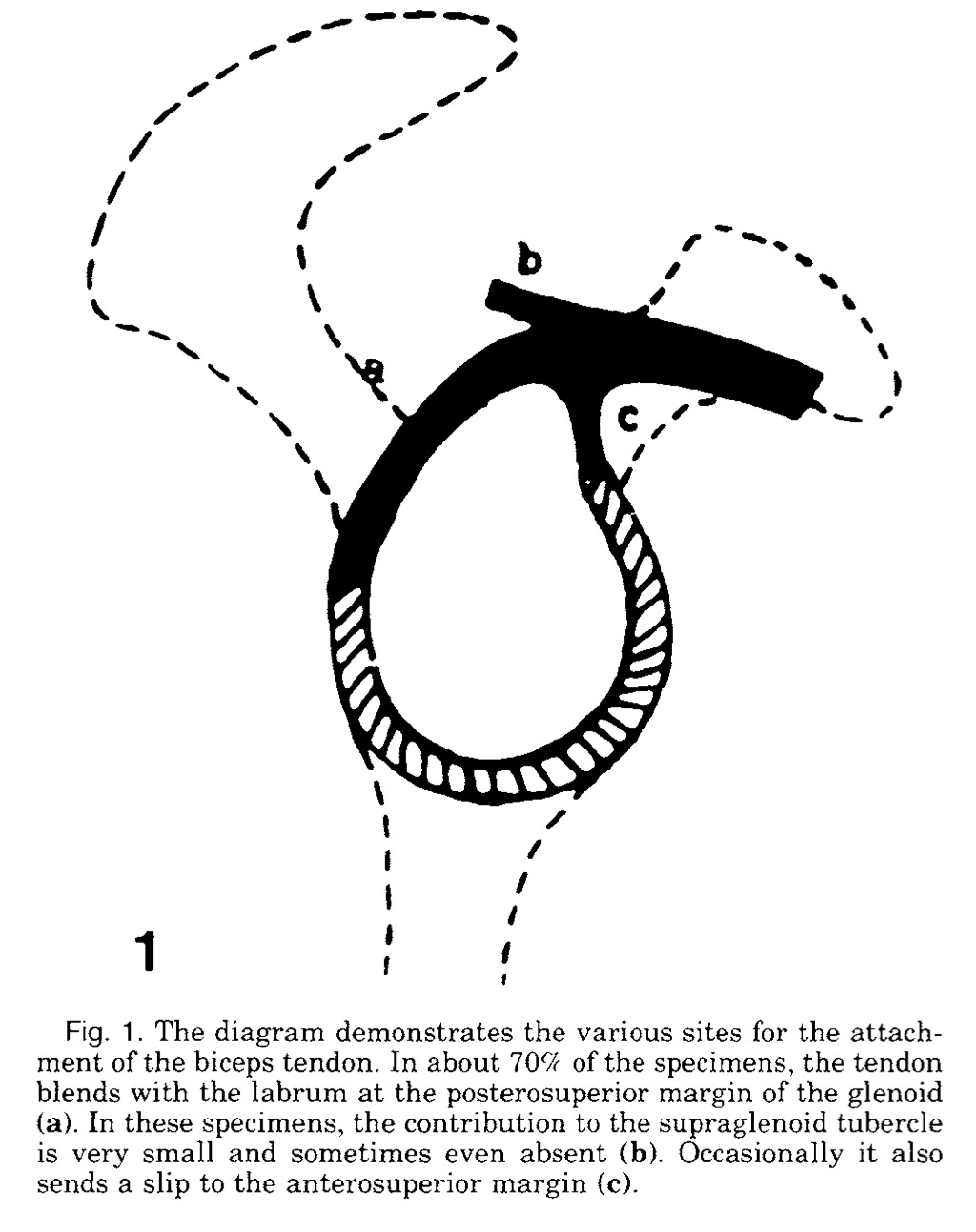

Upon closer assessment, studies find variations in terms of which head seems to contribute more fibers into either distal attachment. More proximally, the long head seems to mesh and become indiscernible with the superior labrum and the supraspinatus tendon. While the short head has been shown to lend with the anterior shoulder capsule as well as attaching to the coracoid process.

Mechanics:

With this in mind we need to consider the influence that this muscle will have on the scapula, humerus, and radius. As well as the potential for influencing other structures and movement strategies.

With increased concentric orientation proximally, this has the potential to create a tensile force bringing the scapula down as well forward into an anterior orientation. This position will result in a compressive force on the top and anterior aspect of the shoulder and rib cage. It will also create a compressive force on the front of the shoulder capsule based on its attachment. When measuring ER/IR and 90 degrees of abduction, the above influences have the potential to limit both ER and IR of the shoulder.

Distally it creates both a tensile and compressive force on the front of the elbow, limiting extension, and a tensile force that would bring the entire radio-ulnar-humeral complex into ER. If you’ve followed other posts about elbows and pitchers this is usually associated with an expansion of the medial elbow.

Depending on the magnitude of the forces, these forces being created by the bicep can have influences that we’ll see in an example below.

Context:

Jared is a MLB reliever who I have posted about in the past. In the above video I demonstrate movement limitation before and after the manual intervention. Below are postural photos demonstrating wide spread changes following the manual intervention as well.

The purpose behind this session wasn’t to help him with any shoulder discomfort, he didn’t have any. The goal was to help his body make desired mechanical changes. If you recall from prior posts (No Guts, No Glory. Waterbed Drills for Pitching Mechanics) Jared struggles with delaying his move down towards home plate and stay back on his left side for longer. Creating too much force down and right too quickly.

By reducing the concentric activity of the L bicep, he is now in a better position to delay when he delivers that force. A good way to describe the influence his bicep was having would be to imagine that you’re standing next to a handrail, you grab onto that hand rail with your left hand, and you actively try to pull yourself down into the ground. You’d probably feel your shoulder drop, and you’d feel much more force going down into that left leg.

Greig, H. W., Anson, B. J., & Budinger, J. M. (1952). Variations in the form and attachments of the biceps brachii muscle. Quarterly Bulletin of Northwestern University Medical School, 26(3), 241–244.

Bharambe, V. K., Kanaskar, N. S., & Arole, V. (2015). A study of biceps brachii muscle: Anatomical considerations and clinical implications. Sahel Medical Journal, 18(1), 31–37.

Pal, G. P., Bhatt, R. H., & Patel, V. S. (1991). Relationship between the tendon of the long head of biceps brachii and the glenoidal labrum in humans. Anatomical Record, 229(2), 278-280.

Share this post